Thursday, January 19, 2006

But Why This Church ...

Brian's comment below is neither "simplistic" nor "naive." Rather, in noting that "the church is necessary because God's actions in Christ and in the Holy Spirit have made it so" he states a foundational truth. Foundational truths are essential, but they have the nasty habit of raising as many questions as they answer. This one begs the question of which church is necessary? In other words, what manifestation or expression of church necessarily arises out of God's actions in Christ and the Spirit? On the other hand, what manifestation or expression of church arises, instead, out of needs for human security, out of human fear, out of cultural expectation, and out of theologies or Christologies shaped and informed by such fear, insecurity and cultural expectation? How can we tell the difference?

Tuesday, January 17, 2006

What Church?

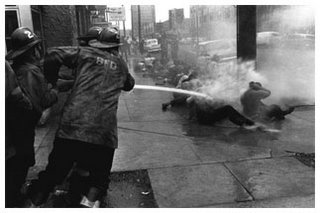

The first comment from yesterday's post raises the next question: what is the church? Our Reformed confessional heritage can be both gift and burden for all such questions, but on this one it does offer much to consider. I believe it is the Scots Confession that says the marks of the true church are that the word of God is rightly proclaimed and the sacraments are rightly administered. I can't help a day-after-King-Day provocation: perhaps the fire hoses of Birmingham were baptism, the lunch counter sit-ins were the Lord's Supper, and "I have a dream" was the word proclaimed.

In addition to the marks of the church, he constitution of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) names certain purposes or ends of the church. Among them is "exhibiting the kingdom of God to the world." The Beloved Community is one compelling image of that kingdom.

Of course there are many ways to be the church and few will ever be called to look much like the Civil Rights Movement, but, as Martin Luther suggested, a church that "gives nothing, costs nothing and suffers nothing is worth nothing." Radical generosity, costly grace and redemptive suffering may just be additional "marks of the church."

Nevertheless, no matter what vision pertains -- whether conservative or progressive, Reformed or Roman, movement or institution -- the present moment demands that we think seriously about the question: is the church necessary? Why? Why not? What do you think? How does your own experience with church shape your response?

Monday, January 16, 2006

Why Church?

When I began this blog in November of 2004 I posted an e-mail from a friend who was asking, essentially, "why bother with church at all?" Martin Luther King Day is a perfect opportunity to grapple again with that essential question.

Why consider the necessity of the church on King Day? After all, King was often extremely critical of the church. In his Letter from the Brimingham Jail King wrote that "the judgement of God is upon the church as never before. If the church of today does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authentic ring, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an errelevent social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. I am meeting young people every day whose disappointment with the church has risen to outright disgust."

On the other hand, I have always suspected that the Civil Rights Movement, at its best moments, was, precisely, the church at its best. King suggested as much in ending his famous letter when he prophesied that "One day the South will recognize its real heroes. ... They will be the young high school and college students, young ministers of the gospel and a host of their elders courageously and nonviolently sitting-in at lunch counters and willingly going to jail for conscience's sake. One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters they were in reality standing up for the best in the American dream and the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage" -- in other words, they were being the church.

Indeed, as Douglas John Hall notes in Why Christian?, "The first Christians were not thinking in institutional terms at all, they were thinking in terms of a movement" (page 127). Of course, as both the early church and the Civil Rights movment learned, if any movement is to be sustained over time various institutional forms become necessary. The movement gave birth to, among other institutions, the NAACP, the Congress on Racial Equality, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The first Christians, and all of the rest of us for 2,000 years, have built, reformed, reshaped and rebuilt the church in thousands of institutional incarnations.

This King Day comparison is not without incongruencies, of course. The Civil Rights movement was not an entirely faith-based enterprise. It did not requiring creedal statements or confessions, (although it issued manifestos, including many of King's speeches, that are confessional statements). Nevertheless, I think it is a useful comparison because it can help us ask central questions about the church: in what way is it a movement? to the extent that it is a movement, toward what is it moving? what institutional forms, liturgies and traditions serve the direction of the movement? which ones distract from that direction?

Ultimately, these questions help refine our approach to the central question my friend's e-mail raised: is the church necessary and, putting my own, self-interested cards on the table, why does it remain necessary?

Why consider the necessity of the church on King Day? After all, King was often extremely critical of the church. In his Letter from the Brimingham Jail King wrote that "the judgement of God is upon the church as never before. If the church of today does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authentic ring, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an errelevent social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. I am meeting young people every day whose disappointment with the church has risen to outright disgust."

On the other hand, I have always suspected that the Civil Rights Movement, at its best moments, was, precisely, the church at its best. King suggested as much in ending his famous letter when he prophesied that "One day the South will recognize its real heroes. ... They will be the young high school and college students, young ministers of the gospel and a host of their elders courageously and nonviolently sitting-in at lunch counters and willingly going to jail for conscience's sake. One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters they were in reality standing up for the best in the American dream and the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage" -- in other words, they were being the church.

Indeed, as Douglas John Hall notes in Why Christian?, "The first Christians were not thinking in institutional terms at all, they were thinking in terms of a movement" (page 127). Of course, as both the early church and the Civil Rights movment learned, if any movement is to be sustained over time various institutional forms become necessary. The movement gave birth to, among other institutions, the NAACP, the Congress on Racial Equality, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The first Christians, and all of the rest of us for 2,000 years, have built, reformed, reshaped and rebuilt the church in thousands of institutional incarnations.

This King Day comparison is not without incongruencies, of course. The Civil Rights movement was not an entirely faith-based enterprise. It did not requiring creedal statements or confessions, (although it issued manifestos, including many of King's speeches, that are confessional statements). Nevertheless, I think it is a useful comparison because it can help us ask central questions about the church: in what way is it a movement? to the extent that it is a movement, toward what is it moving? what institutional forms, liturgies and traditions serve the direction of the movement? which ones distract from that direction?

Ultimately, these questions help refine our approach to the central question my friend's e-mail raised: is the church necessary and, putting my own, self-interested cards on the table, why does it remain necessary?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)