Saturday, December 23, 2006

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Dining While Gay, and Other Crimes

"The members of Truro and the Falls Church have now declared that belonging to a church that permits gays and lesbians to become bishops is too great a tax on their conscience, while belonging to a church that believes gay people should be imprisoned for eating together in public is not.

"I can suggest three reasons that Bishop Martyn Minns and his flock may have taken this decision. The first is naked bigotry. The second is a willingness to trade the human rights of innocent Africans for a more advantageous position in the battle for control of the Anglican Communion. The third is a profoundly distorted understanding of who Jesus was and what he taught.

"I'd like to believe that the last of these reasons explains the majority of the votes, because I recognize that my own salvation may depend on God showing mercy to those of us who are sincere in our misapprehensions.

"But, if Bishop Minns and his followers do, indeed, believe that gay Nigerians should be imprisoned for visiting a restaurant together, they need to inform us whether they believe gay Americans should be imprisoned for similar activities. And if they do not support the criminalization of such behavior in the United States, they need to explain why they favor--or, at the very least, acquiesce--in depriving Nigerians of rights that Americans enjoy."

Monday, December 18, 2006

Who Do We Shoot? And How ...

When confronted with the overwhelming complexity of Dust Bowl agricultural economics, Pa Joad in The Grapes of Wrath, asked a great question: "who do we shoot?" Pa Joad came to mind when reading an article by Daniel Schrag, a Harvard climate scientist, lamenting the state of public debate about climate change. Having testitfied at a Senate hearing this month, Schrag wrote, "As our leaders accept the outrageous spectacle I saw the other day as just a normal day in Congress, we will have to take the first step without them." I just wonder how. How do citizens of a democracy -- so called -- take effective steps on huge, systemic issues when the public institutions of the democracy no longer function? Sure, if the people lead, the leaders will follow -- but how, exactly, does that happen on a scale large enough to make a difference? Who do we shoot? Just asking.

When confronted with the overwhelming complexity of Dust Bowl agricultural economics, Pa Joad in The Grapes of Wrath, asked a great question: "who do we shoot?" Pa Joad came to mind when reading an article by Daniel Schrag, a Harvard climate scientist, lamenting the state of public debate about climate change. Having testitfied at a Senate hearing this month, Schrag wrote, "As our leaders accept the outrageous spectacle I saw the other day as just a normal day in Congress, we will have to take the first step without them." I just wonder how. How do citizens of a democracy -- so called -- take effective steps on huge, systemic issues when the public institutions of the democracy no longer function? Sure, if the people lead, the leaders will follow -- but how, exactly, does that happen on a scale large enough to make a difference? Who do we shoot? Just asking.Wednesday, December 13, 2006

Reimagining Christianity 2.0

Affirmation 10 holds that loving ourselves includes claiming the sacredness of both our minds and our hearts, recognizing that faith and science, doubt and belief serve the pursuit of truth. This seems, again, straightforward and in accordance with the scriptural command to love God with heart and mind and soul. But one doesn't have to look far at all to find faith, science and the pursuit of truth utterly confused. Whether the subject is creationism (check this scary site), atomic warfare, or sexual orientation, the views of science and the "literal word of God" (an interesting phrase when you consider who uses it and who doesn't so much anymore) are held to be at odds in the minds of many.

Affirmation 10 holds that loving ourselves includes claiming the sacredness of both our minds and our hearts, recognizing that faith and science, doubt and belief serve the pursuit of truth. This seems, again, straightforward and in accordance with the scriptural command to love God with heart and mind and soul. But one doesn't have to look far at all to find faith, science and the pursuit of truth utterly confused. Whether the subject is creationism (check this scary site), atomic warfare, or sexual orientation, the views of science and the "literal word of God" (an interesting phrase when you consider who uses it and who doesn't so much anymore) are held to be at odds in the minds of many.The heart breaking results of such confusions are plain to see in a piece in the New York Times on gay evangelicals trying to find a faith home. Robert Gagnon, quoted in the Times piece, is correct about one thing: "the concept gay evangelical is a contradiction.” Of course, he's wrong about everything else. The concept is a contradiction precisely because we have for too long allowed the rest of the key words that he uses -- authority of scripture, self-affirming, evangelical -- to be construed narrowly in a discourse controlled by a conservative orthodoxy. The entire enterprise of reimagining Christianity, it seems to me, aims at wresting control of the discourse away from such narrow-minded voices.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

Reimagining Christianity 1.9

Affirmation 9 holds that "loving ourselves includes ... basing our lives on the faith that, in Christ, all things are made new, and that we, and all people, are loved beyond our wildest imagination – for eternity."

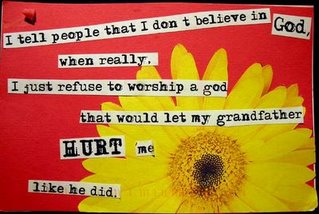

Affirmation 9 holds that "loving ourselves includes ... basing our lives on the faith that, in Christ, all things are made new, and that we, and all people, are loved beyond our wildest imagination – for eternity."I suppose that means, "God is good, all the time ... for all time." Pretty basic -- until we actually try living as if it were true, or until we raise questions of theodicy (the problem of evil, as suggested by the picture.)

Both challenges are fundamental. As Bonhoeffer observed, the knowledge that God loves my worst enemy as much as God loves me must challenge the way I view the enemy. At the same time, the knowledge of what the worst in us can result in -- pain, suffering, injustice, war -- challenges our understanding of the goodness of God.

So, how do we trust this affirmation, and how do we live out of it?

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Good Intentions and the Road to Hell

I went searching for an image for the "road to hell" and came across, instead, the image here of the road to the Bahgdad airport. It is certainly a hellish route made that way by the intentions -- good or ill -- of the empire and its insurgent opposition in Iraq.

My own intentions had nothing to do with such a route -- just looking for an imaginative way of saying "sorry for being dark for a while."

I don't know if a week with a board meeting, a Presbytery meeting and a newsletter deadline can be called one of "good intentions," but it has certainly overloaded a few circuits, including the virtual ones of the blog.

But the show will go on again soon. I promise. Thanks for checking back.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Happy Thanksgiving!

Reimagining Christianity 1.8

Hm, seeking understanding and calling forth the best from ... our enemies? Sounds risky and naive to me -- a call likely answered with a suicide bomb (do I play the conservative fear card well?)

I'm reminded of something Tony Campolo wrote after 9-11: "What has made it the very worst of times is that it is becoming more and more difficult to get away with talking about Jesus within the church. If you dare to quote Jesus in some Christian gatherings, you are likely to encounter hostility. ... If, without the required apologies, you should quote what Jesus had to say about how to treat enemies, it should be expected that one or more in the congregation will stand up and walk out. This is not a time when there are ready ears for words such as, 'Love your enemies and do good to those who would hurt you.'" (In Strike Terror No More.)

I had lunch this afternoon with some folks from the Rumi Forum, an organization that fosters interfaith dialogue between Muslims and nonMuslims. They spoke of both the difficulty and importance of such work in the post 9-11 world.

At a moment when some in the Christian world consider Islam itself the enemy of the West, seeking deeper mutual understanding and calling forth the best from one another sounds a bit less like risky naivete and a bit more like practical politics -- as the Confession of 1967 suggested a few years back.

Monday, November 13, 2006

Reimagining Christianity 1.7

Affirmation 7: Loving our neighbors includes preserving religious freedom and the church’s ability to speak prophetically to government by resisting the commingling of church and state.

Affirmation 7: Loving our neighbors includes preserving religious freedom and the church’s ability to speak prophetically to government by resisting the commingling of church and state.Last week, on a stunningly beautiful autumn day, we loaded up the kids and drove down to Charlottesville to visit Monticello. It was the perfect setting to contemplate the separation of church and state.

In 1802, Jefferson wrote, "Believing... that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their Legislature should 'make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,' thus building a wall of separation between Church and State."

Of course, Jefferson was wary also of the church mingling in the affairs of state. In 1815, he wrote, "Whenever... preachers, instead of a lesson in religion, put [their congregation] off with a discourse on the Copernican system, on chemical affinities, on the construction of government, or the characters or conduct of those administering it, it is a breach of contract, depriving their audience of the kind of service for which they are salaried, and giving them, instead of it, what they did not want, or, if wanted, would rather seek from better sources in that particular art of science."

Clearly, he did not think too highly of preachers!

But what happens when "lessons in religion" happen to turn on questions of justice? What is the role of the church in a time of war? What should the church say in the face of unjust economic structures? What of "love of neighbor" pushes us to an understanding of neighborliness that transgresses societal or even legal definitions such as Jim Crow laws, slavery, women's suffrage, same-sex relationships?

Just wondering ... that's all. And certainly no offense to Mr. Jefferson, who is one of my heroes.

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Tending Hearts and Bending Arcs

I know many of our hearts are hurting this morning as a result of the passage of the marriage amendment in Virginia yesterday. But no result of a ballot measure – for better or for worse – is going to herald the coming of the kingdom. The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. Sometimes it seems longer than others, and this is one of those times for GLBT folks and their allies here. But this I know: our fundamental equality does not rise or fall on the result of any election, because each and every one of us is created equally in the image of a loving God.

I know many of our hearts are hurting this morning as a result of the passage of the marriage amendment in Virginia yesterday. But no result of a ballot measure – for better or for worse – is going to herald the coming of the kingdom. The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. Sometimes it seems longer than others, and this is one of those times for GLBT folks and their allies here. But this I know: our fundamental equality does not rise or fall on the result of any election, because each and every one of us is created equally in the image of a loving God. Let our hearts be reassured by that unshakeable conviction, and let us tend to each other’s hearts with compassion.

While the news on this front was bad, the broader political picture is more hopeful as progressive voices were heard and progressive candidates elected in many places across the country. So maybe the arc bends a bit more today.The image here -- note the arc -- comes from the Center for the Advancement of Nonviolence.

Now is the time for a season of nonviolence -- especially after the passage of an ugly and violent amendment.

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

Reimagining Christianity 1.6

Affirmation 6 holds that loving our neighbors means standing, as Jesus does, with the outcast and oppressed, the denigrated and afflicted, seeking peace and justice with or without the support of others.

Affirmation 6 holds that loving our neighbors means standing, as Jesus does, with the outcast and oppressed, the denigrated and afflicted, seeking peace and justice with or without the support of others.This is the heart of an authentic theology of incarnation. While classical Reformed understandings of the incarnation focus on the challenge of holding God and the human person, Jesus, in creative and saving relationship, this affirmation pushes us to think of incarnation as an unfolding reality in the world.

This affirmation pushes us to think about location: where do we stand, and where does Jesus stand? Taking the gospels seriously -- especially Matthew 25 -- makes it clear that Jesus stands with the outcasts and oppressed, the poor and the sick, those seeking peace and justice. If we want to stand with him, if we feel any desire to know him and be known by him, we have to go where he is.

Monday, November 06, 2006

Bending the Arc

Friday, November 03, 2006

blogging on ... the antichrist

Lecturing is a lot like blogging. Suppose I said, "Bush is the Antichrist"? Would anyone respond with a comment?

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Vote No! A Pastoral Plea: Pass It On

In the name of a narrow and restricted view of marriage based on an impoverished reading of scripture, leaders of the Religious Right are encouraging their followers to support this amendment.

Marshall-Newman is bad law, and such support is bad theology. Bad law and bad theology make a dangerous and volatile mix that Virginia does not need.

Marshall-Newman is bad law because it fails the first measure of good law: clarity of purpose. When two of the commonwealth's statewide elected officials come to diametrically opposed and fundamentally incompatible conclusions about the effects of a proposed constitution amendment -- as Gov. Tim Kaine and Attorney General Bob McDonell have -- you have a recipe for clogged courts and judicial confusion.

Supporting such bad law in the name of one-sided readings of brief passages of scripture taken out of their historical contexts is bad theology. Blaming a loving, grace-filled God for our own human tendency to fear those who are different from ourselves is even worse theology. Acting on those fears in ways that will hurt others is nothing short of demonic. Just as we opponents of Marshall-Newman say "read the whole thing," a faithful response to scripture requires that we read fully as well. A full reading reveals a God in love with all of creation and humankind made fully -- each and every one of us -- in the image of the divine.

As the full text of the proposed Marshall-Newman amendment reads, the amendment could deny legal rights and protections to the more than 100,000 unmarried couples in Virginia -- roughly 90 percent of whom are heterosexual. Domestic violence protections have been threatened in Ohio under an almost identical constitutional amendment.

In other words, a vote for ballot question 1 (the Marshall-Newman amendment) will affect someone you know and it could well hurt them. Passage of the amendment will not help anyone.

That many Virginia families are struggling no one denies. That many Virginia marriages are strained is equally undeniable. Only 17 states have higher divorce rates. Ten percent of Virginians live below the federal poverty rate. Surely these are signs that point to real suffering.

But Marshall-Newman will do nothing to support Virginia families or strengthen marriages in the Commonwealth.

Rather, it seems a smokescreen designed to focus attention on scapegoats instead of on the poverty of ideas that plagues the commonwealth.

In my own Presbyterian tradition we say that we are the church Reformed and always open to being reformed according to the will of God and the movement of the Spirit. In other words, we share a deep conviction that God is not through with us.

Virginia has an opportunity next Tuesday to speak boldly from that very conviction. God is calling forth a new vision of the commonwealth.

God calls us to loving and faithful relationships. Marshall-Newman inscribes hate-filled discrimination into the constitution.

God calls us to be filled with grace and mercy. Marshall-Newman is full of judgment and condemnation.

God calls us to build a commonwealth of belovedness. Marshall-Newman rests on a poverty of compassion.

God is not through with us.

With that deep conviction, I urge you to vote No on ballot question 1.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Reimagining Christianity 1.5

Affirmation 5: Loving our neighbor includes engaging people authentically, as Jesus did, treating all as creations made in God’s very image, regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, age, physical or mental ability, nationality, or economic class.

So, is this the gospel or just a manifesto for identity politics? Do we have to treat meanies as creations made in God's very image? Does that mean no more "mean people suck" bumper stickers? How about those with whom we profoundly disagree? Beyond praying for those who persecute us, do we have to engage them authentically? What might that look like?

The rubber hits the road here, and I'm not so sure I like it. It might require me to hold in my heart people I don't like very much, after all, not every neighbor is loveable.

In fact, last night -- Halloween -- some of them stayed hidden behind closed doors, and missed out seeing my middle child trick-or-treating dressed up as ... me! Clerical collar and all. Pretty scary, I assure you.

Monday, October 30, 2006

Yea, Rick!

Rick Ufford-Chase is at it again. Way to go, Rick!

Arizona Daily StarPublished: 10.30.2006

Guest Opinion: Rick Ufford-Chase -- No on Prop. 107

Proposition 107 would explicitly deny any "marriagelike" benefits to persons who are not married and would constitutionally define marriage as being available only to persons of opposite gender. Like the broader society, the faith community is deeply divided on this issue.

My experience as the highest elected official of the Presbyterian Church (USA) from June 2004 to June 2006 gave me a glimpse into the passion and divisiveness of this debate. Though it is clear that there is currently no consensus in our churches to broaden the definition of marriage, our denomination has been clear that we will not become unwitting participants in any movement to isolate gay and lesbian persons as a group, nor will we condone discriminatory practices against the lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender community from our legislative, executive or judicial branches of government.

This is entirely consistent with our denomination's historic advocacy for women, persons of color, undocumented persons, and those who live with mental or physical disabilities, all of whom also face the possibility of discrimination because of who they are.

I long for the day when all who desire to make a lifelong commitment to one another are able, as I am, to do so within the bonds of the covenant of marriage. Someday, it could happen. After all, the biblical story is full of examples of God's people being surprised by what God had in mind for them.

We Presbyterians believe that God is constantly being revealed to us in ways that challenge, trouble and occasionally delight us. For that reason, I will continue to be in dialogue with my sisters and brothers with whom I disagree about this matter.

As people of faith, all of whom are struggling to be faithful to their understanding of God, we must find respectful ways to wrestle with this and many other issues that divide us. However, what we must not tolerate are laws motivated by hate or discrimination, or that single out an entire class of people to be treated differently from the rest of us.

Prop. 107 would take away domestic-partner benefits such as health insurance from public employees. It would remove domestic-violence protections from unmarried persons. It makes simple things like the right to visit a loved one in the hospital impossible.

Questions of how marriage is defined will continue to be debated within our faith communities and across our society. In the meantime, let's assure that our laws embody the best of what our country has always been: a safe haven for those who might be targeted elsewhere because of who they are or what they believe.

Let's honor our country's history as a place of tolerance, mutual forbearance, care and concern for all members of our communities. Those are values that all of us, both in and out of the church, ought to be able to affirm.

Please, vote "no" on Proposition 107.

Rick Ufford-Chase was the Moderator of the 216th General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA). He now serves as the Executive Director of the Presbyterian Peace Fellowship. Write to him rickuffordchase@gmail.com.

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Reimagining Christianity 1.4

Affirmation 4: Loving God means expressing our love in worship that is as sincere, vibrant, and artful as it is scriptural.

What might that entail for a community that calls itself progressive, inclusive, diverse? What, to begin with, constitues "sincere worship"? If you Google the phrase, you get more than 16,000 hits. Now that probably says as much about the search engine as it does about the interest in worship, but clearly a lot of folks are writing about this from perspectives that range from evangelical Christian to Muslim to Native American spirituality to Budhism.

My favorite Biblical definition of worship comes from Paul's letter to the Romans, where he says, "I appeal to you therefore, brothers and sisters, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship. Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect."

Sincere worship, it seems, has to do with discernment -- with listening for and coming to understand how God calls us to live transformed lives.

There are just as many hits on "vibrant worship," and just as much confusion over what it means. Perhaps any worship in which people come to hear and understand something true, powerful and transformative is, by definition, vibrant.

There are far fewer hits on "artful worship." Why do you suppose that is? What would such worship look like? feel like? sound like? I hope it would be full of beauty, which is why I snagged the painting above for all to look at. It's called Creation.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Reimagining Christianity 1.3

Affirmation 3: Loving God includes celebrating the God whose Spirit pervades and whose glory is reflected in all of God’s Creation, including the earth and its ecosystems, the sacred and secular, the Christian and non-Christian, the human and non-human.

Perhaps that is another way of asking "WWJD?" -- what would Jesus drive? One would think that this affirmation would be essentially noncontraversial, what with evangelicals joining the conversation and even the green movement.

Of course, when one affirms that the glory of God is reflected in the non-Christian as well as the Christian one is treading dangerously close the the radical Paul -- in Christ there is no Jew or Greek. At its deepest level, Paul's call for unity is not a call for "conversion" to Christ but rather an affirmation of Paul's faith that the reality of Christ marked God's decisive "yes" to all the world, not simply to the small part of the world that related to God through the community of practice gathered around the traditions of Judaism.

I suppose, though, that a call to reflect our deepest convictions in the way we actually live -- what we drive, what we purchase, how we tread on the planet -- is probably a far more difficult challenge for most of us that grappling with the theological implications of this affirmation. So, how do we make these decisions? What are we driving? What toys are we using right now, to read and comment?

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Pastors & Politics

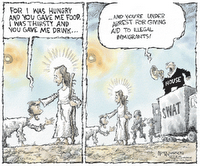

It's not surprising, but it's still worth reading about how the so-called Christian Right is pushing voters toward the Republican party. I particularly love the advice to tell folks that Jesus would be more concerned about gay marriage than about war and peace. Now there is no endorsement of any party or candidate implied here, but I do think it's time to be afraid, be very afraid. There's an election coming and the "Christians" are on the loose. (The cartoon comes from the blog of Bill Sanders, retired cartoonist from the Milwaukee Journal.)

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

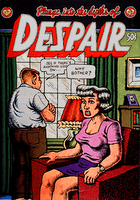

Midweek Despair

The news is never good these days. War and rumors of war. Climate catastrophe in the making. Scandal. Violence. Injustice. The Braves missed the playoffs. It is enough to bring despair.

We rest uneasily between two countervailing pressures. One imagines a way out of the present malaise by longing to go back to an imagined past that never was. The other longs to imagine a way forward. Yet the work of imagination necessary for that way forward is blocked by the desolation of the very institutions necessary for that imaginative work.

For example, take Congress ... please. The people's house will not or cannot not tend to the people's work. It will not because too many of its members are beholden to those who long to go back to that imagined past. It cannot because its structures are corrupted by money and vested interests that do not want a way forward.

For another example, take the church ... again, please. It will not or cannot cast a vision and do the work of imagination necessary in these times. It will not because it is too timid and too tepid to shake the foundations of the status quo. It cannot because, again beholden to or cowed by those who long to go back, it no longer attracts those who have been graced by the prophetic imagination so crucial for such a moment.

At such a time as this ... well, it's a good time for a mystery novel and a doughnut.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Reimagining Christianity 1.2

Perhaps this stuff seems tame. Maybe it's old hat. Or perhaps it is, in its own subtle way, so powerful as to be overwhelming. Certainly the first affirmation, that the way of Christ is not the only way to God, is heretical according to a traditional orthodoxy. Next to that, this second affirmation does not seem to say much.

On the other hand, as Karl Barth observed, "to clasp the hands in prayer is the beginning of an uprising against the disorder of the world."

Indeed, prayer is not seeking to bend God's will to that of the world, but rather seeking to bend ourselves to God's will for the world. If we pray that God's will be done "on earth as it is in heaven," then we are calling forth a social order of love and justice out of the chaos and disorder of a world in which power flows from the end of a gun or the bottom line of a bank statement.

Daily prayer and meditation are the power practices of an alternative community of compassion that casts a vision for a politics of justice. There is, indeed, a politics of prayer and it runs counter to the prevailing politics of empire.

Affirmation 1 may challenge the orthodoxy of Christian theology. Affirmation 2 challenges the orthodoxy of empire.

Friday, October 06, 2006

About Last Night ...

Here's what I said.

For too long, those who oppose acceptance and equality of LGBT people and their families have misappropriated the terms pro-marriage and pro-family in the service of an anti-gay agenda. Too often they have based their theft of these terms on midguided, selected reading of scripture. But somehow they missed the part about "letting justice roll down like a mighty water and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream."

Right here, right now we reclaim the language of marriage and family, of justice and of righteousness, as our own.

Authentically pro-marriage laws extend the rights, responsibilities and values of marriage to all adults in committed and loving relationships regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Authentically pro-family laws sustain, uphold and protect the diversity of human families throughout God's good creation.

We call on all those who support justice and equality to reclaim the true meaning and values of marriage and family, and to let the justice waters roll down across the Commonwealth on Nov. 7.

The journey to justice is often long and seldom smooth. But when we do the work of love, we shorten the journey and smooth the way. The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice. We are the ones to bend the arc. Thank you for being here. Thank you for your energy and your hope. Now go and bend the arc a little closer to justice.

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

Reimagining Christianity 1.1

This week the blog returns, off and on, to the joyous work of being site of an on-line adult Christian education conversation. CW will continue to interrupt with random comments on whatever happens to strike his curious brain, but "major" posts will focus for the next six weeks or so on topics related to Reimagining Christianity. The jumping off point for the conversations comes from the Phoenix Affirmations.

This week the blog returns, off and on, to the joyous work of being site of an on-line adult Christian education conversation. CW will continue to interrupt with random comments on whatever happens to strike his curious brain, but "major" posts will focus for the next six weeks or so on topics related to Reimagining Christianity. The jumping off point for the conversations comes from the Phoenix Affirmations.Affirmation 1 says this: for Christians, loving God includes walking fully in the path of Jesus, without denying the legitamcy of other paths God may provide humanity.

For a long time now, there has been a kind of "lazy lay liberalism" that affirms this point. It has been liberal in accepting the validity of other paths. It has been lay in that the attitude is broadly shared "in the pews." Alas, it has been "lazy" in that it has been articulated as a doubt concerning orthodoxy rather than as a principle of Christian theology based in scripture and in our understanding of God.

The image above -- found when I googled "salvation" -- should tell you all you need to know about what conservative evangelicals think about affirmation 1. If not, then, imbedded in an otherwise obnoxious article, First Things provides a helpful description of what conservatives think of lay liberalism. They pretty much think we need to be saved from our own thoughts and that they are the ones to do it.

So, for the sake of beginning a conversation, a few questions:

First, what's your "first-blush" response to affirmation 1?

Second, where might you turn in scripture to support this view? (In other words, how might this affirmation transcend the label of "lay liberalism"?)

Third, how might such an affirmation change the church?

And for those of you spying on progressive pastors and looking for grounds for heresy charges let me just help you out: I absolutely believe that following Jesus does not mean salvation for all can be found only in Jesus. God's thoughts are higher than our thoughts. God's ways higher than our ways. There is nothing more human than imagining that our way is the only way.

At the risk of "truthiness" and with appropriate cautions, there is an informative piece on universal salvation on Wikipedia.

Saturday, September 30, 2006

Proud, for once, to be Presbyterian

There are times -- many times -- when I am angry at the denomination in which I serve. There are time -- many times -- when I am saddened by it. And there are times -- many, many times -- when I am simply bored by it.

But today I am proud of the church, or, at least, of the immediate past moderator of our General Assembly. Elder Rick Ufford-Chase was arrested in DC this week leading a witness for peace and protest against the war in Iraq. The picture here is from the "die in" in the rotunda of one of the Senate office buildings. Way to go Rick!

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Feeling American

I am feeling so American this week. First, we took a trip -- very American -- over the weekend. We wound up driving a big-butt SUV (full-size Dodge Durango, a testosterone machine if ever there was one) because our minivan died an untimely death last week. Driving an SUV makes you want to squish things -- like small cars, especially hybrids!

While on the road we heard from our mechanic. He told us about the van using the same tone a doctor might in saying, "sir, you've got a malignant mass in your brain."

Or, as Dr. McCoy would say, "it's dead, Jim."

So, still feeling very American, we went car shopping. Actually, being 21st-century Americans we managed this entirely on Craigslist, quite likey the greatest invention ever.

Of course, something about Craigslist is quite un-American -- or, at least not too much like America has become in the post-war years. As you enter the marketplace -- perfectly American -- you also enter a community -- not so American anymore. I've met some of the most interesting people in buying guitars, bikes and furniture and in selling or giving away books, TVs and assorted things we've outgrown.

This time, we met a woman who works for EPA. She was selling a hybrid Honda. Car selling and buying is most American. Working for the common good through a public agency ... highly questionable. Hybrids? Well, maybe not so much, yet.

So now we've donated away to public radio the washed up van and we're the downsized drivers of one hot little Honda. God bless America!

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

A Jesus Agitation

When I lose sleep it’s because Jesus’ words haunt my own life. If, as Jesus said, the poor are blessed, how do I, I who live comfortably among the richest one percent of the global population, participate in this blessedness?

If, as Jesus said, the meek are blessed, how do we Christians who dwell in the heart of the American empire participate in this blessedness?

If, as Jesus said, the mourners are blessed, how do we, who live in a culture built on security and the denial of death, participate in this blessedness?

If, as Jesus said, those who hunger and thirst for justice are blessed, how do we who profit so much from systemic economic injustice, participate in this blessedness?

If, as Jesus said, the merciful are blessed, how can we who live in a culture blinded by one eye traded for another, participate in this blessedness?

If, as Jesus said, the pure of heart are blessed, how do we who live in a hypersexualized, violent and utterly banal culture participate in this blessedness?

If, as Jesus said, the peacemakers are blessed, how do we, in whose name and with whose money endless war if waged, participate in this blessedness?

If, as Jesus said, those who are persecuted for the sake of justice are blessed, how can we who seem way too comfortable to speak of being persecuted participate in this blessedness?

Monday, September 18, 2006

Vote No!

In about six weeks the good people of the Commonwealth of Virginia will vote on one of those constitutional amendments “to protect the sanctity of marriage.” Well my own marriage feels relatively sanctified … or something, without such language, but it does make me wonder why some folks feel compelled to write such things. As thrice-married Rep. Bob Barr was famously asked when he proposed the federal defense of marriage act some years ago, “which of your marriages are you defending?”

Why is this the current front line on the culture wars? Martin Luther King observed that many “say that war is a consequence of hate, but close scrutiny reveals this sequence: First fear, then hate, then war, and finally deeper hatred.”[1]

Following King, one might suggest an even broader sequence: first fear, then hate, then injustice – and then war or codified bigotry or institutionalized economic injustice.

The fear of terror – certainly grounded in experience – has so easily become a hatred of the Arab-Muslim world fueled by prejudices and willed ignorance that combine to make the path to war all too easy for our nation to follow. And now we can see so clearly the spiraling cycle of deeper hatred.

The fear of gays and lesbians – grounded in ignorance and fueled by bigotry – becomes a hatred that makes the path to constitutional amendments all too easy for our nation to follow. And I do not even want to imagine the spiraling cycle of deeper hatred these politics of fear will engender.

The fear of the outcast, the marginalized, the homeless poor – grounded, perhaps, in our own deep-seated economic fears – becomes a disdain functionally indistinguishable from hatred that blames victims for their plight and makes the choices that lead to greater injustice seem inevitable. And deeper hatred will continue its spiral.

So vote “no” on all of these fear-filled proposals, and strike a blow for fearless hope.

[1] This version of the quote comes from Quotable King, Steve Eubanks, ed. (

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Agitation for Today

Why is it that the blowhards from the so-called Christian Right never want to post the Sermon on the Mount on the front lawns of the courthouses across the land? Just wondering, that's all. And, still just wondering, doesn't that thing pictured here have the look of a graven image? Perhaps it would work better to tattoo the commandments on the butt of a golden cow. Surely then we would have a righteous nation.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

The Spiritual Politics of Yes & No

The primary confession of Christian faith, Kurios Christos, or Christ is Lord, is a political claim even as it is a confession of faith whose repetition is a spiritual practice. In the time of the early church, when that simple confession emerged, the Roman Empire required every citizen to make an annual public profession of loyalty that said “Kurios Caesar” or Caesar is Lord. To say “Christ is Lord” in such a world was an act of dissent and even disloyalty to the Empire.

As the machinery of war grinds on, questions of dissent and disloyalty press in. The vice president accuses war critics of aiding the terrorists. The flag is waved higher and higher. The terror threat level will rise just as surely as the sun as the November elections draw closer.

In the midst of all that, to say Kurios Christos threatens the empire. As Robert McAfee Brown put it, “Caesars don’t like that one bit, whether they reside in Rome or in Washington. So the First Commandment, ‘You shall have no other gods before me,’ and the earliest Christian confession, ‘Christ is Lord,’ are making the same claim in different language, a claim around which all of us not only can, but must, rally. In the name of saying yes to what is ultimate for us, we must be prepared to say no to whatever falsely claims that place of ultimacy. To say yes to the true God is to say no to the idols, wherever and whatever they are.”[1]

Obviously, such saying yes and saying no is a political act, but just as clearly, it is a spiritual practice of Christian faith for it reshapes and reforms us closer to the image of Christ.

Just as the heart of the earliest confession of the faith is deeply political, so too is the heart of our most cherished prayer. When we pray “thy kingdom come … on earth as it is in heaven,” what we’re saying is truly revolutionary: let us live as if God were the ruler of the earth and not the kings and generals and presidents and CEOs whose actions dominant. As Marcus Borg said, “The Kingdom of God is about God’s justice in contrast to the systemic injustice of the kingdoms and domination systems of the world.”[2]

Saying the Lord’s Prayer is saying “no” to the powers and principalities and saying “yes” to God. It is most clearly a deeply spiritual practice of the faith for it ought to transform us, but it is also just as significantly a political gesture that aims at transforming the world.

Even in the deeply personal act of prayer, then, we recognize that while God is, indeed, personal, God is not private. As Jim Wallis says, the “personal God demands public justice as an act of worship. We meet the personal God in the public arena and are invited to take our relationship to that God right into the struggle for justice.”[3]

Of course, one wants to know how? How do we engage in a spiritual practice of social action and protest that does not simply devolve into competing factions shouting beyond one another in endless rounds of mounting anger? We do well to keep in mind William Sloan Coffin’s caution that a “politically committed spirituality contends against wrong without becoming wrongly contentious.”[4] That must involve the deep conviction that those we oppose in the social arena are also beloved children of God, and that we must always seek to find and honor the Christ in them even as we work to achieve an often radically different vision of social arrangements.

Then there is that question of vision. What is the vision of justice toward which we aim and on what is it grounded? Put simply, provisionally and decidedly nonprogramatically, the Biblical vision of justice is this: sorting out what belongs to whom and returning it.[5]

So, for example, in a world of plenty food belongs to those who are hungry; in an economy of abundance work belongs to those who seek jobs; in the 21st century health care belongs to those who are sick, shelter belongs to those who are homeless, and clothing belongs to those who are naked; in our nation’s cities good schools belong to children left behind; in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) ordination belongs to those who are called; in the Commonwealth of Virginia and across these United States marriage belongs to those who are in love regardless of sexual orientation; in Northern Ireland, in Israel, in Palestine, in Darfur, in Iraq and everywhere that plow shares still give way to swords and shields peace belongs to us all.

It is far past time for sorting this stuff out. It is far past time.

It is far past time to move beyond religion that focuses only on the next world, that insists on an unbiblical distinction between the sacred and the secular, and that, as a result, blesses the status quo even as that status crushes millions beneath the weight of injustice, oppression, sexism, heterosexism, racism, militarism and neoconservative globalism.

It is far past time to recognize that the doing of justice is the primary expectation of the God of the Bible.[6]

[1] Robert McAfee Brown, Speaking of Christianity (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1997) 43.

[2] Marcus J. Borg, The Heart of Christianity (San Francisco: Harper, 2003) 132-3.

[3] Jim Wallis, God’s Politics (San Francisco: Harper, 2005) 40.

[4] William Sloan Coffin, Creedo (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 2004) 69.

[5] Walter Brueggemann, in Brueggemann, Parks, Groome, To Act Justly, Love Tenderly, Walk Humbly (New York: Paulist Press, 1986) 5.

[6] Brueggemann, 5.

Friday, September 01, 2006

Check this Out

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Fascism, Anyone?

Here's another Common Dreams piece worth the read as the term fascism gets tossed around in the political discourse of the moment.

Although the article does a fine job of reminding us of what fascism really looks like, I'm not sure the word has a lot of use anymore. It's historical precedent is lost to most folks and it has become like the "H-bomb" of calling someone "Hitler." It stops conversation and ends education -- although Lewis Lapham's recent piece in Harper's may be an exception.

Rather than calling the present powers-that-be fascist, would it be more useful to show people precisely how the interests of the people are being subverted to the interests of corporate power? That may be the definition of fascist, but calling Wal-Mart fascist doesn't move the political conversation anywhere when the vast majority of folks feel that they are living on an economic edge that makes finding "always low prices" feel more like a matter of survival than a matter of politics.

Of course, as Roosevelt knew amidst the rise of German and Italian fascism, fear itself is the fertile ground in which fascism's seeds are planted. Toiling in that ground is crucial if we are to move beyond a politics of fear into something more hopeful.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

The Bible and Politics, pt. 6.6

Anabaptist(ic) Theologians: Yoder and Hauerwas

Yoder

John Howard Yoder, a Mennonite, was a theology professor at Notre Dame until his death in 1997. More than any other figure, Yoder brought Anabaptist perspectives on theology, ethics and politics, to the attention of the larger church.

In his groundbreaking book, The Politics of Jesus, Yoder painted a convincing picture of Jesus as a nonviolent radical. Challenging conventional notions of 'politics' as the exclusive domain of the state, Yoder articulated a church-centered politics that is based on the imitation of Jesus' nonviolent way. Because Jesus' way reveals the ultimate goal of history, putting most of our political efforts into following Jesus is quite 'realistic,' contrary to what many 'Christian realists' insist. Likewise, as a sociological institution rooted in the world, the church's politics are public, a light for all the world to see.

As the previous sentence indicates, the church's involvement with politics outside of itself is in the form of witness; the life of the church is to be a sign to the world of what God is doing. In this sense, the Bible as the central document of the church has a direct function politically, in that it shapes the church's witness.

Yoder also examined the language with which the church speaks to society. Although he remained firm that the only thing the church ever says is 'Jesus is Messiah and Lord,' he felt that--since the church is a thoroughly historical, sociological entity--it can do nothing but say those words by using the various languages and concepts of the day. In speaking to the state, this means proposing policies in realistic terms readily understood by the state.

The biblical vision of society, therefore, is to strictly guide the church's practice, but can be communicated to the state in pragmatic terms. For example, though the Bible teaches Christians to be strict pacifists, it is highly unlikely the state would ever adopt such a position; thus Christians are to critique and restrain specific wars as much as possible, not call the state to an ideal which it will easily ignore.

Hauerwas

Hauerwas, a Methodist, was a colleague of Yoder's at Notre Dame before moving to Duke, where he still teaches. Named 'America's best theologian' by Time in 2001, Hauerwas espouses a highly philosophical version of Yoder's theology--with significant differences.

Whereas Yoder maintained the possibility of a faithful church speaking effectively to the state in pragmatic terms, Hauerwas is skeptical of the possibility of the church speaking in any other terms than its own. For Hauerwas, any attempt to change the terminology waters down the content to a point that compromises the church's witness. (It should be noted that Hauerwas claims continuity with Yoder on this subject.)

As a virtue ethicist and follow of Yoder, Hauerwas devotes the vast majority of his efforts to articulating the church practices that form Christians into a different kind of people--a political, public community whose inner life witnesses to the world. The church should eschew political terminology that is easily confused with the world's (like 'justice' and 'rights'), and speak only its 'thick' language of Christian discipleship.

As indicated by Hauerwas's claim of continuity with Yoder on this subject the difference between the two is probably one of degree. As Anabaptist-minded theologians, both work hard to base their vision of social ethics in the church community first, and in the rest of the world (a distant) second. Both are convinced of the necessity of the church to speak the one message it has been given, but Yoder seems more optimistic about the ability to put this message into practical terms that the state can understand and use in its policies.

In terms of this class, these theologians see the Bible's primary political function as shaping the church into a community whose politics exhibits God's reign. When speaking to the state, Yoder is more willing to couch biblical language in other terms, while Hauerwas believes those are the only terms with which we can speak.

Questions:

1) Is the church a primary location for political action? Is it subordinate to the state's politics?

2) How has the Bible functioned to shape the politics of your church community?

3) What do you think about Christians' ability to speak to the state in 'pragmatic' terms? Do Christians only have Christian language, or do we speak Christian messages in other languages?

Sources:

Stanley Hauerwas, Resident Aliens (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1989).

John Howard Yoder, The Christian Witness to the State (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1964).

Yoder, The Politics of Jesus, 2d edition (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994).

Yoder, The Priestly Kingdom (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984).

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

The Bible and Politics, pt. 6.5

Anabaptism

In the last 50 years or so, Anabaptist theologians have made their church’s distinct approach to religion and politics known to the rest of the church. John Howard Yoder and Gordon Kaufmann are perhaps the best known recent Anabaptists, and their students Stanley Hauerwas, Duane Friesen, and Glen Stassen have popularized their treatments of the issue beyond the confines of Anabaptism.

Central to the Anabaptist approach is attention to the church as a primary location for discipleship. In regards to our question, an Anabaptist asks first, ‘How can the politics of the Bible be lived out in the community of the church’ well before asking, ‘How can the Bible be used in political situations outside the church.’ This church-first stance means an Anabaptist response to racism, ecological disaster, or poverty will rely heavily on the church’s own use of the Bible in those situations.

Viewing the church in such a way implies some sort of separation between the church as a political unit, and other political units (such as the

When it does come time to interact with political entities outside of the church, many Anabaptists are pessimistic about using language that is not deeply rooted in Christian tradition. This pessimism comes about from a deep conviction that, through baptism, a Christian’s identity is first and foremost derived from the church. In other words, the primary language of Christians is explicitly Christian, and to attempt a translation would invariably lose much of the meaning that makes Christianity’s politics work. However, because of the priority of the church and it separation from the state, Anabaptists do not go out of their way to tell the state what to do—in biblical or any other terms—and mostly focus on the church’s responsibility to live out a different kind of politics.

Questions:

1) How do you feel about Anabaptism's prioritization of the church? Is the church political? Can political change happen within the church?

2) What do you think about the claim that Christians' primary identity is as Christians? Does this affect how you view your ability to use non-biblical language in politics? Can Christian (and biblical) language be translated for use in politics?

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

The Bible and Politics, pt. 6.4

Leonardo Boff

Boff, a leading Latin American liberationist until his silencing by Rome, envisioned local church communities as communities of the poor organizing to liberate themselves from oppression. Through prayer, Bible study, and social analysis the poor would gain insight into the best ways to undermine and overthrow the capitalist system.

The Bible is thus at the center of political change in Boff's view. And yet for Boff the key to politics is not a knowledge of the Bible, but a commitment to justice. Justice here is conceived of in neutral, historical or sociological terms; as Boff, quoting German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, put it, 'the word of God' we are called to transform the world with 'will be a new language, perhaps quite non-religious, but liberating and redeeming....'

James Cone

'To preach the gospel today means confronting the world with the reality of Christian freedom....Preaching the gospel is nothing but proclaiming to blacks that they do not have to submit to ghetto-existence.'--Again, explicitly biblical terms, but leading to a more general political concept of liberation.

Benjamin Valentin

Valentin is a current Latino liberation theologian working in the US whose work has focused on building coalitions for political change. He works with the concepts of commonality and the public square to advocate the convergence of disparate groups around shared political issues.

In terms of political language, he urges Christians to adopt 'a pragmatic and historicist theological discourse that uses the language of reason and rights in the public sphere, rather than the language of piety, confessionalism, or religious dogmatism.'

This statement is not to negate the necessity of drawing from the symbols and stories of one's religious tradition; on the contrary, Valentin recognizes the importance of such symbols and stories, but hopes they can be developed in an open, constructive way that engages partners of other theological (and non-theological) persuasions.

Any use of the Bible in American politics, we can extrapolate, would have to be in an inclusive way that appeals to Americans who do not share Christian (or Jewish) valuations of the Bible. The goal of the church's political action is pragmatic--social change--so it should focus on joining with others to bring that about rather than trying to fit Bible quotes into speeches.

Sources

Leonardo Boff, Ecclesiogenesis (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1986).

James H. Cone, A Black Theology of Liberation (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1986).

Benjamin Valentin, Mapping Public Theology (Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 2002).

Questions (sorry I've been forgetting about these!)

1. Boff states that the church is a place where the poor organize for liberation. What do you think about this statement? Do you think the Bible speaks to the political situation of the poor and marginalized?

2. The theologians covered here seem to agree that the biblical message is oriented towards practical political liberation. Do you agree? How does your understanding of the biblical message affect how you think it should be used in politics?

3. What do you think about Valentin's distinction between a 'language of reason and rights' and a 'language of piety, confessionalism, or religious dogmatism'? Does such a distinction exist? To what extent does the Bible fit in either category?

Sunday, August 06, 2006

The Bible and Politics, pt. 6.3

Though the phrase ‘liberation theology’ arose from a Latin American Catholic movement in the early 1970s, it is now used as an umbrella term for several groups with similar approaches to theology and politics. Black, feminist, queer, ecological, mujerista (Latina), womanist (black women), minjung (Korean), and other theologies fit under this wide umbrella.

Distinctive about liberation theology is its commitment to reading the Bible and doing theology from the perspective of the poor and oppressed. Liberationists believe the God of the Bible sides with the poor, and thus we should too. Accordingly, liberation theology has focused on organizing the oppressed into faith communities which become bases for prayer, Bible reading, and political action.

Theologically, liberation theologians emphasize the kingdom or reign of God that can be actualized now through revolutionary action on behalf of and with the oppressed. This stance led many early liberationists to support violent revolutions, such as the Cuban revolution and the Sandanista revolt in Nicaragua. More recent liberation theologians tend to advocate theologies of non-violence.

The political rhetoric of liberationists tends to be highly biblical, but it also draws from recent sociological analysis. Liberation theology is usually committed to listening for God’s voice in sources outside the church, so Marx and others are regarded as valuable companions to the Bible in advancing the revolutionary agenda.

Because liberation theology is church-based in practice, its political speech tends to take place in the form of sermons and theological writings; because it is revolutionary in character its political speech tends to take place in churches and other grassroots locations. Nevertheless, its sociological analysis allows it to convey some of its central ideas (e.g., land reform, democracy, anti-capitalism) in broad terms to wider audiences.

On the American political scene, liberation theology is an active force behind many denominational and interfaith advocacy alliances. Through their demonstrations and lobby work, we can see the blend of biblical and non-biblical discourse, political speech that is as unafraid of using the Bible as it is comfortable using more ‘common’ terminology.

Friday, August 04, 2006

The Bible and Politics, pt. 6.2

Neo-Calvinist Theologians: Kuyper and Mouw

Abraham Kuyper

We have already traced some of the broad themes of Kuyper’s theology, but let’s look more specifically at how he addressed the intersection of politics and religion; we can then draw out some hypotheses as to how he might have regarded our question of the use of the Bible in American politics.

Three years before becoming Prime Minister of the Netherlands in 1901, Kuyper delivered the Stone Lectures at Princeton University. His topic was Calvinism and his aim to portray Calvinism as a ‘life system’ that can adequately account for modern issues in art, politics, religion, and academia. In his lecture on ‘Calvinism and Politics,’ Kuyper sets forth his understanding of the sovereignty of God as the only true basis for a government that makes just use of the sword, provides for the social needs of its people, and protects its citizens’ individual liberties.

Because Kuyper saw the Christian God as the foundation of politics, he imagined a government that was entirely Christian. But, as we discussed in the last post, since politics and the church are two separate spheres, individual politicians should not look to their churches for advice on how to govern, but should trust to their personal understandings of their faith.

Overall, Kuyper advocated a politics that adhered strictly to Christianity and the Bible, even if he left politicians to themselves to figure out what those meant. An example from his own life as a political figure can be seen in an editorial he published on labor issues. As he pushes a pro-organized labor agenda, he continually disparages his opponents as going against God’s decrees. To illustrate just what God’s decrees might be, he quotes Psalm 35:10—‘Oh Lord, who is like you? You deliver the weak from those too strong for them!’ The Bible, then, is an acceptable part of political discourse, as long as its use is controlled by (Christian) politicians, not churches.

Richard Mouw

Mouw is the President of Fuller Seminary and a professor of philosophy who draws heavily from Kuyper. He elucidates similar positions to Kuyper’s own about the use of religious language in politics, saying that Christian politicians should avoid seeking out their pastor’s advice on political issues. But, working with categories from anthropologist Clifford Geertz, Mouw pushes for a distinction between the use of ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ language. Mouw thinks the ‘thick’ language of the Christian worldview—the complexities of theological and biblical discourse—should best be left in churches and seminaries, while thin language is used to communicate Christian beliefs to the state in terms the state can understand. In all, Mouw is seeking a basis for common participation in society, something he feels that ‘thick’ language gets in the way of. This position by no means prohibits the use of the Bible in politics, but it does lean away from it.

Abraham Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1931)

Abraham Kuyper, ‘Manual Labor,’ in Abraham Kuyper: A Centennial Reader, ed. James D. Bratt (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998).

Luis E. Lugo, ed., Religion, Pluralism, and Public Life: Abraham Kuyper’s Legacy for the Twenty-First Century (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000).

Richard J. Mouw, He Shines in All That’s Fair: Culture and Common Grace (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001).

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

The Bible and Politics, pt. 6.1

The first theological position to be examined is what is often called ‘neo-Calvinism’ and sometimes ‘Kupyerianism.’ As the latter name indicates, the position is rooted in the life and work of Dutch politician, journalist, educator, and clergyman Abraham Kuyper. Through his various occupations (most of which were held simultaneously), Kuyper attempted to revitalize the ‘Reformed’ theology of John Calvin for his time, particularly stressing Calvin’s doctrine of ‘common grace.’

Common grace—which, incidentally, is not an emphasis in Calvin’s own work—is the belief that God is actively involved in the world to restrain evil and promote some amount of order and flourishing. Neo-Calvinists often quote Matthew 5:45b in support of this doctrine: ‘for [God] makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous.’

Common grace becomes the basis for a political theology when it is combined with a certain understanding of the opening chapter of Genesis. There neo-Calvinists find the ‘cultural mandate,’ God’s command that humans develop societal structures: ‘fill the earth and subdue it’ (1:28). Because human culture is part of God’s created order, then culture is meant to follow God’s designs, and, since God through common grace continues to be active in the world, Christians can participate in culture—including politics—with the purpose of achieving that design.

At this point we might conjecture that neo-Calvinists would encourage the use of the Bible in American politics, since such use might facilitate the ordering of American politics to God’s created design. Nevertheless, one other doctrine enters the neo-Calvinist picture to complicate things. That doctrine, called ‘sphere sovereignty,’ asserts the fundamental integrity of the various aspects of culture. Family, church, government, business, etc. are each separate ‘spheres’ that must be allowed to develop independently without too much interference from the others (government is somewhat of an exception since it works above and between the spheres).

Christians, therefore, are left with a somewhat paradoxical role in politics: they are to engage politics with the hope of ordering it according to God’s design, but they are not to confuse the spheres of church and government. Though, as we will see in the next post, various neo-Calvinists resolve that paradox in different ways, it at least provides us with a rough base from which to build a neo-Calvinist response to the issue of the Bible and politics.

Although the Bible, insofar as God’s intended design for politics can be found in it, is indispensable in shaping Christian political engagement, Christians must be careful to ensure that their political language and actions are sufficiently ‘political’ and not overly ‘religious.’ Thus the neo-Calvinist view assigns the Bible a place in politics, but cautions that its use may violate the separation of church and government spheres. This nuanced position will become more clear in the following post on specific neo-Calvinist theologians.

Friday, July 28, 2006

The Bible and Politics, 5.2

Acts-Revelation

Acts

As a story about the expansion and dispersion of early Christian communities, Acts is as explicitly political as the Gospels. Christians are constantly coming into contact with political officials, and their discourse is often recorded (or ‘created’) by the author. The speeches of Peter (4:8-12) and Stephen (7:2-53) before the temple council are preeminent examples of the use of scripture in political situations. Drawing on the shared narrative of the Jewish scriptures, both Peter and Stephen retell parts of that narrative, naming Jesus as its culmination. Paul continues this pattern of scriptural debate in synagogues around

The Epistles

Since the epistles were written to encourage and guide specific churches in their communal life, there are no examples in them of scripture used to directly address political situations outside of the churches. Nevertheless, many of the epistles seem to counsel churches on how to act within their political settings. Hebrews is an especially interesting example, as it is basically a commentary on Old Testament scripture. Jesus is depicted both as the great high priest who opens up the inner courts of the tabernacle to us, and as the exalted Lord who rules the world and judges its rulers, just as portrayed by Psalms 2 and 110. These meditations are to strengthen the community’s resolve to be a kind of alternative political community that is ‘receiving a kingdom that cannot be shaken’ (Hebrews 12:28). This community is to be marked by the welcome of strangers, care for prisoners, peace, and detachment from money, among other things (see chapters 12-13).

Revelation

Though Revelation is notoriously difficult to interpret, I understand it as a political document denouncing the authority of the

Reflect on the various ways the biblical authors use Scripture in political situations. Are the authors consistent? Are there multiple ways to use Scripture in political settings? Do the uses change with the context?

As always, think about how political situations in biblical times are similar and different to our own (see past posts for questions).

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

The Bible and Politics, 5.1

The Gospels

Today we turn our attention to the use of Scripture in political situations in the New Testament, specifically in the Gospels. Again, since only the briefest of surveys is possible, please fill these ‘lectures’ out with your own thoughts.

From the coming of John the Baptist to Jesus’ death and resurrection, the Gospels place Jesus’ life and ministry firmly within the world of the Hebrew Scriptures. Each of the Gospels regards John the Baptist’s coming as the fulfillment of Isaiah 40:3—John prepares the way for the Lord who comes to gather and feed the people of God. Jesus’ mission is thus framed as ‘political’ from the start, a mission to gather a people and provide them with some basic social services (e.g., feeding and healing). As far as I understand it, a body that administers social services for a gathered people is one way of defining ‘government.’

Jesus does begin to gather, feed, and heal people in

Perhaps the most overt use of scripture for political purposes in the Gospels occurs in the temple action near the end of Jesus’ life. Upon entering the

Questions:

1) Again, think about the similarities and differences between the political structures in Jesus’ day and our own. What would be the location of a ‘temple action’ in our day? How appropriate would it be to quote Isaiah and Jeremiah in a political speech at the capitol building?

2) Here we begin to get into the idea of the church as a political community—if Jesus’ mission was ‘political’ in some sense, what is the political role of the church now? What role does the Bible play in the church’s politics?

Monday, July 24, 2006

The Bible and Politics, 4.4

Here’s the last Old Testament lesson. Later in the week I’ll post two sections on the New Testament, dealing first with the Gospels and then with Acts-Revelation.

Old Testament Writings

The section of the Old Testament known as the Writings covers all the books not in the Torah or Prophets. They are books of history, poetry, song, and story. Because the Writings are so varied, I will make no attempt to cover all of them here. For our purposes, a quick look at Psalms will suffice.

Psalms

There are two primary ways the Psalms reference Scripture: through discussions of the ‘commandments’ (or ‘law,’ ‘decrees,’ ‘teaching,’ etc.) and through stories that retell significant events in Israelite history. Good examples of the first can be seen in Psalms 19 and 119. Both speak of the commandments as guides to follow to achieve the ‘good life.’ Far from being purely ‘spiritual’ or ‘religious,’ these psalms point to the political life of the people of God—measured by the commands found in the Torah—as the locus of faithful worship. The psalms themselves indicate the political nature of following the commands: Psalm 19 is ascribed to King David and is addressed ‘to leaders,’ and the voice behind Psalm 119 is an exile who is persecuted by princes, but who nontheless speaks God’s decrees to kings (119:19, 161, 46).

Several psalms retell significant narratives from the Israelite past, especially the creation and the exodus. Psalm 136 is one example that tells both stories in order to remind God’s people that God is the one that delivers us from hardships—God’s faithful love vanquishes enemies, feeds the hungry, and ‘remembered our low estate’ (136:23-25). Though it’s hard to tell when any of the psalms were written, it’s feasible that story psalms like this one were especially important in the exile and at other times in which the political life of the people of God was imperiled. Singing the Lord’s songs in foreign lands was hard, as Psalm 137 tells us, but it also seemed to be a vital part of maintaining a distinct political identity.

Other Writings

As a guide book of wisdom, Proverbs admonishes rulers and all God’s people to a life of obedience to the commands of the Torah. The history books of Ezra and Nehemiah are about leaders who exemplify such obedience in their quest to restore

In summary, the Writings, like the Prophets, uphold the Torah as the basic template of political life for the people of God. Even when God’s people are in exile—having little or no political sovereignty—they are called to live out God’s commands within their communities.

Questions:

1) In what ways are our political situations similar or different from those of the Israelites in exile? Are we ‘at home’ in a Christian nation? Or are we ‘in exile’ in a foreign land? Do you think the answers to those questions affects how we use the Bible in American politics? Why or why not?